Before answering that question, I'll tell you about an incredibly impressive ethnographic study and field survey. For a one year period, the investigators (Pretus, Hamid et al., 2018) conducted field work within the community of young Moroccan men in Barcelona, Spain. As the authors explain, the Moroccan diaspora is an immigrant community susceptible to jihadist forms of radicalization:

Spain hosts Europe’s second largest Moroccan diaspora community (after France) and its least integrated, whereas Catalonia hosts the largest and least integrated Moroccan community in Spain. Barcelona ... was most recently the site of a mass killing ... by a group of young Moroccan men pledging support for the Islamic State. According to a recent Europol’s latest annual report on terrorism trends, Spain had the second highest number of jihadist terrorism-related arrests in Europe (second only to France) in 2016...

After months of observation in selected neighborhoods, the researchers approached prospective participants about completing a survey, with the assurance of absolute anonymity. No names were exchanged, and informed consent procedures were performed orally, to prevent any written record of participation. The very large sample included 535 respondents (average age 23.47 years, range 18–42), who were all Sunni Muslim Moroccan men.

The goal of the study was to look at sacred values in these participants, and whether these values might affect their willingness to engage in violent extremism. “Sacred values are immune or resistant to material tradeoffs and are associated with deontic (duty-bound) reasoning...” (Pretus, Hamid et al., 2018). The term sacred values doesn't necessarily refer to religious beliefs. One of the most common is the basic human value, “it is wrong to kill another human being.” But theoretically speaking, we could include statements such as, “it is wrong to kill endangered species for sport (or for any other reason).”

In this study, Sacred Values included:

- Palestinian right of return

- Western military forces being expelled from all Muslim lands

- Strict sharia as the rule of law in all Muslim countries

- Armed jihad being waged against enemies of Muslims

- Forbidding of caricatures of Prophet Mohammed

- Veiling of women in public

What were the Nonsacred Values? We don't know. I couldn't find examples anywhere in the paper. It's crucial that we know what these were, to help understand the “sacralization” of nonsacred values, which was observed in an fMRI experiment (described later). So I turned to the Supplemental Material of Berns et al. (2012), inferring that the statements below are good examples of nonsacred values in a population of adults in Atlanta.

- You are a dog person.

- You are a cat person.

- You are a Pepsi drinker.

- You are a Coke drinker.

- You believe that Target is superior to Walmart.

- You believe that Walmart is superior to Target.

But what if the nonsacred values in the present study of violent extremism were a little more contentious and meaningful?

- You are a fan of FC Barcelona.

- You are a fan of AC Milan.

Anyway, to choose participants for the fMRI experiment, the investigators first divided the entire group into those who were more (n=267) or less (n=268) vulnerable to recruitment into violent extremism (see Appendix for details). An important comparison would have been to directly contrast brain activity in these two groups, but that wasn't done here. Out of the 267 men more vulnerable to violent extremism, 38 agreed to participate in the fMRI study. These 38 were more likely to Endorse Militant Jihadism (score 4.24 out of 7) than the general fMRI pool (3.35) and the non-fMRI pool (2.43).1

A battery of six sacred and six nonsacred values was constructed individually for each person and presented in the scanner, along with a number of grammatical variants, for a list of 50 different items per condition. The 38 participants were randomly assigned to one of two manipulations in a between-subjects design: exclusion (n=19) and inclusion (n=19) in the ever-popular ball-tossing video game of Cyberball. [PDF]2

Unfortunately, this reduced the study's statistical power. Nonetheless, a major goal of the experiment was to examine how social exclusion affects the processing of sacred values. I don't know if Cyberball studies are ever conducted in a within-subjects design (perhaps with an intervening task), or if exposure to one of the two conditions is too “contaminating”. At any rate, in real life, discrimination against Muslim immigrants is isolating and causes exclusion from social and economic benefits. Feelings of marginalization can result in greater radicalization and support for (and participation in) extremist groups. At this point in time, I don't think neuroimaging can add to the extensive knowledge gained from years of field work.

Nevertheless, the investigators wanted to extend the findings of Berns et al. (2012) to a very different population. The earlier study wanted to determine whether sacred values are processed in a deontological way (based on strict rules of right and wrong) or in a utilitarian fashion (based on cost/benefit analysis of outcome). As interpreted by those authors, processing sacred values was associated with increased activation of left temporoparietal junction (semantic storage) and left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (semantic retrieval). Berns et al. suggested that “sacred values affect behaviour through the retrieval and processing of deontic rules and not through a utilitarian evaluation of costs and benefits.” Based on those results, the obvious prediction in the present study is that sacred values should activate left temporoparietal junction (L TPJ) and left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (L VLPFC).

Fig. 3A (Pretus, Hamid et al., 2018).

Fig. 3A shows that only the latter half of that prediction was observed, and there was no explanation for the lack of activation in L TPJ. Instead, there was a finding in R TPJ in the excluded group which I won't discuss further.

Of note, the excluded participants rated themselves as being more likely to fight and die for nonsacred values, compared to the included participants. This was termed “sacralization” and now you can see why it's so important to know the nonsacred values. Are we talking about fighting and dying for Pepsi vs. Coke? For FC Barcelona vs. AC Milan? Not to be glib, but this would help us understand why social exclusion (in an artificial experimental setting) would radicalize these participants (in an artificial experimental setting).

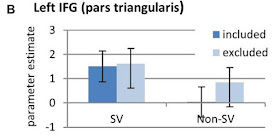

Fig. 3B (Pretus, Hamid et al., 2018). Nonsacred values activate Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG, aka VLPFC) in the excluded group, but not in the included group. This was interpreted as a neural correlate of “sacralization”.

Another interpretation of Fig. 3B is that the exclusion manipulation was distracting, making it more difficult for these participants to process stimuli expressing nonsacred values (due to increased encoding demands, syntactic processing, etc.). Exclusion increased emotional intensity ratings, and decreased feelings of belongingness and being in control. This distraction could have carried over to the task of rating one's willingness to fight and die in defense of values.

Even if we say the brain imaging results weren't especially informative, the extensive ethnographic study and field surveys were a highly valuable source of data on a marginalized group of young Muslim men at risk of recruitment by violent extremist groups. It's a vicious cycle: terrorist attacks result in greater discrimination and persecution of innocent Muslim men, which has the unintended effect of further radicalization in some of the most vulnerable individuals. To conclude, I acknowledge that my comments may be out of turn because I have no authority or expertise, and because I'm from a country with an appalling record of discriminating against Muslims.

Footnotes

1 I was a bit confused by some of these scores, because they changed from one paragraph to the next, and differed from what was in Table 1. Perhaps one was a composite score, and the other from an individual questionnaire.

2 I've written extensively about whether Cyberball is a valid proxy for social exclusion, but I won't get into that here.

References

Berns GS, Bell E, Capra CM, Prietula MJ, Moore S, Anderson B, Ginges J, Atran S. (2012). The price of your soul: neural evidence for the non-utilitarian representation of sacred values. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 367(1589):754-62.

Pretus C, Hamid N, Sheikh H, Ginges J, Tobeña A, Davis R, Vilarroya O, Atran S. (2018). Neural and Behavioral Correlates of Sacred Values and Vulnerability to Violent Extremism. Front Psychol. 9:2462.

Appendix

Modified from Table 1 (Pretus, Hamid et al., 2018).

[The] measures included (1) a modified inventory on general radicalization (support for violence as a political tactic) based on a prior longitudinal study on violent extremist attitudes among Swiss adolescents (Nivette et al., 2017); (2) a scale on personal grievances and previously used on imprisoned Islamist militants in the Philippines, and Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka (Webber et al., 2018); (3) a scale on collective narcissism which has been shown to shape in-group authoritarian identity and support for military aggression against outgroups (de Zavala et al., 2009); (4) a self-report delinquency inventory adapted from Elliott et al. (1985), based on the disproportionate number of Muslim European delinquents who join jihadist terrorist groups (Basra and Neumann, 2016); and (5) a series of items assessing endorsement of militant jihadism (“The fighting of the Taliban, Al Qaida, ISIS is justified,” “The means of jihadist groups are justified,” “Attacks against Western nations by jihadist groups are justified,” “Attacks against Muslim nations by jihadist groups are justified,” “Attacks against civilians by jihadist groups are justified,” “Spreading Islam using force is every part of the world is an act of justifiable jihad,” and “A Caliphate must be resurrected even by force”) that we combined into a reliable composite score, “Endorsement of Militant Jihadism”...

No comments:

Post a Comment